How COVID-19 Affects the Body

The Science Behind a New Threat

In January 2020, around the time World Health Organization labeled the novel coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency, medical researchers around the globe began racing to understand COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.1 Since then, COVID-19 has gone from a mystery illness to something more familiar, as troves of scientific studies have helped reveal how the virus affects the body. New insights about the disease emerge almost daily. Still, experts remain puzzled by some aspects of COVID-19.

“We have learned a considerable amount about this particular strain of coronavirus: its symptoms, transmission patterns, and long term effects,” said BayCare Chief Medical Officer Dr. Nishant Anand. “But we still have much to learn.”

This article is intended to provide some of the latest scientific knowledge about how the new coronavirus affects the body. Due to the urgency of the COVID-19 crisis, many researchers have bypassed the traditional route of rigorously peer-reviewed journals and have instead published their findings in pre-print journals. For that reason, many of the latest findings have not been peer-reviewed. To ensure you’re well-informed about this quickly developing topic, we will update the article as new information emerges.

Quick Links

Use these links to navigate to important sections of this article.

Coronaviruses are invisible to the naked eye. It takes a high-powered microscope to see the crown-like spikes that give these viruses their name (corona means “crown” in Latin). The viruses use these spikes to latch onto and pry into living cells, where they multiply before leaving to infect more cells throughout the body.2 To avoid catching COVID-19, it’s critical to prevent the virus from entering the body in the first place.

The nose and throat are considered the key entry points for the new coronavirus.3 Once inside, the virus attaches to biological hooks that appear on the surface of certain types of human cells. Those hooks, called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, are up to 700 times more prevalent on the odor-sensing cells that line the inside of the upper part of the nose, adding to a growing body of evidence suggesting that odor-sensing cells play an important role in the virus’s initial assault.4, 5

After commandeering nasal cells, the virus replicates and attempts to spread further into the body. In the early days of infection, the body’s immune system should kick into action to fight back the virus. However, if the immune system is unsuccessful, viruses will move down the windpipe towards the lungs, where COVID-19 can turn deadly.6

Symptoms

Initial Symptoms

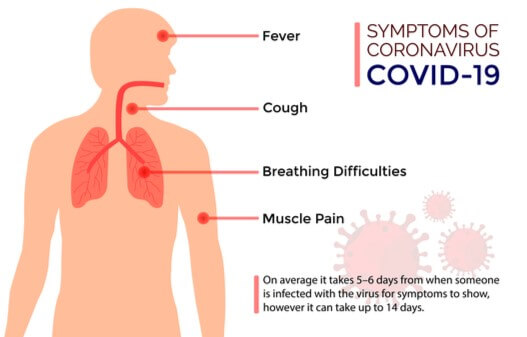

A wide range of symptoms occur in patients with COIVD-19. The most common symptoms include:7, 8

● Dry cough

● Fever or chills

● Fatigue

Less common symptoms include:

● Headache

● Loss of taste or smell

● Muscle or body aches

● Sore throat

● Conjunctivitis (pink eye)

● Congestion or runny nose

● Skin rash

● Nausea or vomiting

● Diarrhea

Serious symptoms include:

● Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

● Chest pain or pressure

● Loss of speech or movement

If you experience any of the symptoms above, please immediately self-isolate and contact your physician.

QUICK FACTS:

Average time from exposure to symptoms: 6 days9

U.S. case-mortality rate: 3%10

Asymptomatic cases: about 40%11

Severe Symptoms

Although COVID-19 is a respiratory disease, meaning it primarily impacts the lungs, it has been shown to affect organs and functions throughout the body. And while most people experience mild to moderate symptoms from COVID-19, the disease can have severe impacts. Some of the more severe cases of COVID-19 can result in the following.12

Immune system

The immune system plays a critical role in defending the body from disease, but it can sometimes harm the body by overreacting to fend off infection. Many of the most severe cases of COVID-19 are a result of overreactions from the immune system. These overreactions are known as “cytokine storms,” after the chemical molecules that guide healthy immune responses.13 During cytokine storms, immune cells can attack healthy tissues, which can result it in blood clots, blood pressure drops, and organ failure.14

So-called “first-responder” immune cells, which typically react quickly to signs of virus in the body, respond slowly in severely ill COVID-19 patients, suggesting that compromised immune systems account for some of the most serious cases of COVID-19.15

Lungs

The lungs are considered ground zero for COVID-19. When the coronavirus reaches these organs, it attacks ACE2-rich cells that line air sacs in the lungs.16 The immune system ratchets up its defenses to neutralize the virus-infected cells. This process can overcrowd the already weakened air sacs and reduce a patient’s oxygen levels, resulting in coughing, fevers, and breathing problems. Patients may contract pneumonia as the air sacs fill with fluid.17

In more severe cases, COVID-19 patients may develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a form of lung failure, and may require ventilators to help breathe.18 ARDS can be fatal. Survivors may suffer long term scarring in the lungs.19

Heart and blood

Heart cells are rich in ACE2 receptors, the new coronavirus’s main point of entry, which helps explain why the virus has been discovered in both heart tissues and heart muscle cells.20 Little is known about how the virus attacks the heart, but cardiac issues such as heart failure and abnormal heart rhythms in some COVID-19 patients are thought to be the result of the body’s inflammatory response to infection.21

Early reports suggested that blood type might play an important role in the severity of COVID-19 cases. Recent reports have challenged that notion, however, finding no correlation between certain blood types and COVID-19.22

Brain

A number of brain-related conditions have been seen in COVID-19 patients, including strokes, seizures, and brain fog, which may be the result of inflammation, organ failure, or oxygen deprivation caused by the virus.23, 24, 25 Research suggests that the new coronavirus may have the ability to infect brain cells, suggesting that the virus may have a direct impact on the brain.26, 27

Eyes

Conjunctivitis, or pink eye, has been observed in some of the sickest COVID-19 patients, in some cases including nearly one-third of hospitalized patients.28 However, pink eye has also been the sole sign of the disease in some patients, leading some researchers to suggest people suffering from conjunctivitis should seek testing.29, 30

Who Is At Risk?

Who Is At Risk?

It’s important to note that many people who become infected with the new coronavirus show few or no symptoms of COVID-19. Early reports found that 80% of COVID-19 patients showed mild symptoms. Recent Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates suggest that around 40% of infected individuals are asymptotic, showing no symptoms at all. Patients with vulnerable immune systems and existing conditions such as heart and lung disease often have the most severe responses to COVID-19.31

The CDC provides a weekly summary of COVID-19 activity, including data about the vulnerability of certain groups.32

Age – Older adults are at higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Patients over the age of 65 are most likely to be hospitalized and most likely to die from COVID-19.33

Race – Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native people are approximately 4.7 times more likely to be hospitalized than non-Hispanic White people.34 Black and Hispanic people are approximately 4.6 times more likely to be hospitalized than non-Hispanic White people.35

Gender – While men and women appear equally susceptible to contracting COVID-19, men are more likely to die from the disease.36 The reason may be that women mount better immune responses than men to the new coronavirus infection, while the female hormone estradiol may help fend off infection.37, 38

-

Article References

- Timeline - COVID-19. World Health Organization. April 27, 2020.

- Novel coronavirus structure reveals targets for vaccines and treatments. National Institutes of Health. March 3, 2020.

- Waradon Sungnak et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nature Medicine. April 23, 2020.

- Mengfei Chen et al. Elevated ACE2 expression in the olfactory neuroepithelium: implications for anosmia and upper respiratory SARS-CoV-2 entry and replication. European Respiratory Journal. July 21, 2020.

- Waradon Sungnak et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry genes are most highly expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells within human airways. aRxiv. March 13, 2020.

- Sonja Bartolome. Life cycle of a coronavirus: How respiratory illnesses harm the body. University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. April 2, 2020.

- Coronavirus. World Health Organization.

- Symptoms of Coronavirus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 13, 2020.

- COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 10, 2020.

- Mortality Analyses. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine.

- COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 10, 2020.

- Coronavirus. World Health Organization.

- Qing Ye et al. The pathogenesis and treatment of the `Cytokine Storm' in COVID-19. Journal of Infection. April 10, 2020.

- Marco Cascella et al. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19). StatPearls. August 10, 2020.

- Study reveals immune-system deviations in severe COVID-19 cases. Stanford Medicine. August 11, 2020.

- Inge Hamming et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. The Journal of Pathology. May 7, 2004

- Panagis Galiatsatos. What Coronavirus Does to the Lungs. Johns Hopkins Medicine. April 13, 2020.

- Zhe Xu et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. February 18, 2020.

- Panagis Galiatsatos. What Coronavirus Does to the Lungs. Johns Hopkins Medicine. April 13, 2020.

- Gaetano Pietro Bulfamante et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptional activity in cardiomyocytes of COVID-19 patients without clinical signs of cardiac involvement. medRxiv. August 26, 2020.

- Cynthia Weiss. How does COVID-19 affect the heart? Mayo Clinic. April 3, 2020.

- Christopher A. Latz et al. Blood type and outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Annals of Hematology. July 12, 2020.

- Alexander E. Merkler et al. Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs Patients With Influenza. JAMA Neurology. July 2, 2020.

- Ali A. Asadi-Pooya. Seizures associated with coronavirus infections. Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy. May 11, 2020.

- Charlotte Huff. Delirium, PTSD, brain fog: The aftermath of surviving COVID-19. American Psychological Association. July 1, 2020.

- C. Korin Bullen et al. Infectability of human BrainSphere neurons suggests neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2. ALTEX - Alternatives to Animal Experimentation. Jun 26, 2020

- Bao-Zhong Zhang et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects human neural progenitor cells and brain organoids. Cell Research. August 4, 2020.

- Ping Wu et al. Characteristics of Ocular Findings of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmology. March 31, 2020.

- Sergio Zaccaria Scalinci et al. Conjunctivitis can be the only presenting sign and symptom of COVID-19. IDCases. April 24, 2020.

- Marvi Cheema et al. Keratoconjunctivitis as the initial medical presentation of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. April 10, 2020.

- Zhonghua Liu et al. [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China]. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. February 20, 2020.

- COVIDView: A Weekly Surveillance Summary of U.S. COVID-19 Activity: a . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2020.

- Older Adults and COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 11, 2020.

- COVIDView: A Weekly Surveillance Summary of U.S. COVID-19 Activity: a . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2020.

- COVIDView: A Weekly Surveillance Summary of U.S. COVID-19 Activity: a . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2020.

- The COVID-19 Sex-Disaggregated Data Tracker. Global Health 50/50.

- Takehiro Takahashi et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature. August 26, 2020.

- Ute Seeland et al. Evidence for treatment with estradiol for women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv. August 24, 2020.